Finding Atlantis

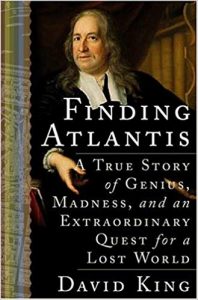

Finding Atlantis, A True Story of Genius, Madness, and an Extraordinary Quest for a Lost World, by David King. Published by Three Rivers Press, an Imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, New York, 2005.

Finding Atlantis is a 309-page book about Olof Rudbeck (Swedish, 1630-1702). The author writes that when Rudbeck was around the age of forty he began making careful studies of the old maps of Scandinavia, and he threw himself into the new world he was envisioning, Atlantis. “The lost world of Atlantis, Rudbeck was growing convinced, had actually been in Sweden! Its capital was in fact just outside the university, in a place called Old Uppsala.”

“Many Greek and Latin writers had recorded impressions about the Hyperboreans, and a number of Swedish thinkers had started to wonder if this enigmatic nation might have been located in the far north of Sweden.” Olof Rudbeck had no doubt about it.

The young Olof is described by the author as an almost inexhaustible optimist. He studied music, medicine, anatomy and dissection, and in 1655 he was offered a position with the medical faculty of the Uppsala University. He designed and helped construct a large university building, an arena-like Theatrum anatomicum or “anatomy theater.” He is today credited with the discovery of the lymphatic system (although a contemporary had made the discovery at the same time). Through his interest in plant life he created a large botanical garden, a work he regarded as a privilege. The garden is still in existence today in Uppsala and is known as the Linnaeus Garden, after a student of Olof Rudbeck the Younger, Carl Linnaeus. Rudbeck’s “measurements of the age of old monuments and graves by the thickness of the humus accumulated over them… anticipated the methods of modern archaeology.”

In keeping with his prosperous life, Olof married Vendela Lohrman, and according to the author’s Notes, this was by all accounts a happy marriage and the couple were blessed with seven children.

By July of 1670, however, the university began having serious financial problems, and Rudbeck, then a full professor and the rector of the university, was heavily criticized by his colleagues for his excesses, e.g., the size of the anatomy theater, and his increasingly costly search to prove that Plato’s Atlantis was in Sweden. There was also serious opposition to Rudbeck’s recognition of Cartesianism (René Descartes, 1596-1650, died in Stockholm). Rudbeck’s interest in Descartes would seem to indicate that he was not a man out of his time, nor was he losing his faculties in the Hyperborean mists.

Eventually accused of mismanagement, “Rudbeck delivered a thundering statement about how much he had donated to the university he loved and demanded to be released from his administrative duties.” Some of the colleagues involved in the accusations would become his lifelong enemies.

Fortunately, Rudbeck had garnered the patronage of Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, Lord High Treasurer, High Chancellor and Lord High Steward of Sweden. In his youth, he had also met Queen Christina, monarch of Sweden, 1632 to 1654. Later, in 1675, he wrote the music for the coronation of young King Charles XI “… and sang the piece himself in Uppsala Cathedral in such a way that his thundering voice was said to overpower some twelve trumpets and four kettledrums playing with all their might.” The king, then learning to play the drums, was very impressed.

Olof Rudbeck’s great work, Atlantica, is a 3000-page treatise in four volumes. The first volume was published in 1679, as he neared his fiftieth birthday, and the last was published in 1702, the year that he died. The author both opens and concludes the book with a description of the great Uppsala fire of 1702. Rudbeck sacrificed his own house, including his printing press, inventions, instruments, excavation discoveries, woodcuts, and unsold copies of Atlantica, to help save the cathedral, the castle and the university.

David King has written Finding Atlantis in a somewhat popular style, keeping the narrative and some difficult subjects as light as possible. The book has numerous old illustrations and maps, and many of the quotations that head the sixteen chapters are drawn from the work of popular, well-known individuals. For example, heading Chapter One is a quote from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes: “My dear fellow, life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind of man could invent.” Some of the other quotations offered are from Benjamin Franklin, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Charlie Chaplin, T.E. Lawrence, and Mark Twain. However, the thorough research that the author undertook – partly in Sweden – to assure the accuracy of his work is revealed at the end of the book in 40 pages of Notes for each of the sixteen chapters and the epilogue.

The paperback cover of the book, which shows Rudbeck’s portrait sinking down under the pressure of Atlantean structures and rocks, and with its reference to “Madness” in the subtitle, is an unfortunate choice. It does not do justice to Olof Rudbeck, his love of life, and his great achievements. He was certainly not “mad” in any sense of the word and can only be admired for his devotion to his profession, his beloved Sweden, and to the lost Paradise known as Atlantis. After all, according to the quote by Rudolf Steiner at the end of The Shadow of Atlantis review, the people of Scandinavia and Sweden, together with the elemental kingdoms, could very well have remodeled their part of the world after the lost island of Atlantis, which now constitutes the bed of the Atlantic Ocean.

For further information – and Olof Rudbeck’s full portrait – see Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olaus_Rudbeck