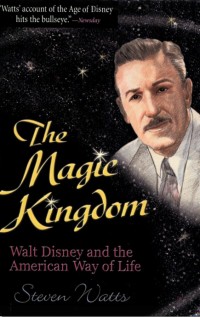

Pearl Harbor: FDR Leads the Nation into War

By Steven M. Gillon

By Steven M. Gillon

Published by Basic Books, Perseus Books Group, New York, 2011 Click to Buy this Book!

Author Steven M. Gillon wastes no words in this gem of a history book. From Chapter 1 through the end of the Epilogue the book is only 188 pages in length and very effectively follows a central theme that focuses on the reactions of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), and those around him, from the time they first learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, at 1:47 p.m. on December 7, 1941, until the following day, when Roosevelt delivered his war message to a joint session of Congress that began with the words: “December 7th, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy.” Steven Gillon is a Professor of History at the University of Oklahoma and the Resident Historian for The History Channel. The television medium with its time restrictions has perhaps influenced this concise account of a day’s duration within a history for which “there is no shortage of books.” The author has also intended his examination of this 24-hour time period to address conspiracy theories: “The public’s fascination with conspiracy theories has distorted much of the writing about Pearl Harbor. The conspiracy theories popped up even before the war was over, with the appearance of John Flynn’s self-published The Truth About Pearl Harbor, and they have continued up to the present, with the 1999 release of Robert B. Stinnett’s Day of Deceit. Most of these books focus on a single question: Did FDR use the attack on Pearl Harbor as a ‘back door’ to war? In other words, was FDR the mastermind behind a massive government conspiracy to push a reluctant nation into battle?” But these conspiracy theories lack credibility: “All the evidence shows that FDR and the men around him were genuinely shocked when they learned of the attack. They may have been naïve and gravely misjudged Japanese intentions and capability, but they were not guilty of deliberate deception.” However, in the Notes section near the end of the book, on page 191, the author admits that “… Although it defies the rules of common sense and lacks evidence, the ‘back door’ theory refuses to go away,” and he suggests further reading on the troublesome topic, the 2003 publication, A Date Which Will Live: Pearl Harbor in American Memory, by Emily S. Rosenberg.

Further along in this review some anthroposophical light, from the lectures of Rudolf Steiner, will be cast on present-day conspiracy theory conundrums.

In the first two chapters of Pearl Harbor, the author combines details of Roosevelt’s daily routine on the morning of December 7th with accounts of the complex history that preceded the disaster. The accounts include descriptions of the rise of Roosevelt’s political career; his initial support for Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations; the Great Depression of the 1930s; Roosevelt’s first term as President beginning in 1933; restrictive isolationist Congressional legislation; Germany’s Blitzkrieg and the beginning of World War II in Europe; Roosevelt’s “Lend-Lease” Program for providing Britain with war matériel; and Japanese expansion of its influence in Asia, its emergence as a major military power, and its signing of a treaty — the “Tripartite Pact” — with Germany and Italy. In 1940, in response to continuing escalation of Japanese intent, Roosevelt relocated the Pacific Fleet from California to Pearl Harbor in Oahu, west of Honolulu, “deliberately to provoke a Japanese attack” according to Stinnett, but most likely because it was a more strategic defense position. (In the midst of these enormous crises of office, Roosevelt suffered a personal loss when his mother, Sara, passed away in September of 1941, hence the black armband he wears in the cover photograph. In addition, FDR had to give attention in November to a United Mine Workers’ strike.) By November of 1941 it was considered likely that Japan would attack British outposts in the Pacific. On November 27th, warnings were sent to the army and navy commanders in Hawaii, Lieutenant General Walter Short and Admiral Husband Kimmel, that Japanese hostile action was possible at any moment: “This dispatch is to be considered a war warning … Negotiations with Japan … have ceased, and an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days.” Roosevelt had repeatedly appealed to the emperor of Japan, Hirohito, for prevention of hostilities, but his last message was not received by the emperor until a few minutes before planes appeared in the skies over Oahu.

Chapter 3 describes the delivery of an intercepted Japanese document to Roosevelt and his trusted friend and adviser, Harry Hopkins, on the evening of December 6th. The document allowed for no chance of a diplomatic settlement with the United States. “This means war,” Roosevelt said to Hopkins, but both agreed that the United States would not make the first overt move, but would allow the enemy to “fire the first shot” on American forces. How else could the full support of the American people be enlisted? They were certainly not anticipating the extent of the Pearl Harbor disaster or the lapses of its military leaders. Admiral Harold “Betty” Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, had received a copy of the message that evening, but thought that the commanders in Hawaii had been sufficiently warned and that Japan was most likely to strike in the Philippines. The 24-hour account as such, from the morning of December 7th, begins on page 36 of Chapter 3. More »