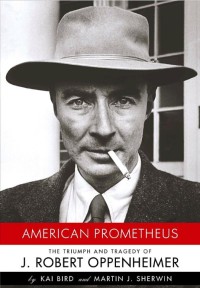

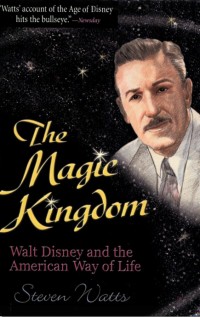

The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life

By Steven Watts

By Steven Watts

University of Missouri Press, First Paperback Printing, 2001 Click to Buy this Book!

In the Introduction of this 526-page biography of Walter Elias Disney (1904–1966), Steven Watts, Chairman of the History Department at the University of Missouri-Columbia, describes some of the challenges involved in the immense undertaking of this project: the sheer scope of Walt Disney’s lifework, an achievement that always depended upon the work of other artists; the extreme divergence of Disney’s admirers and denouncers (“I don’t know anything about art.”); and his powerful and continuing influence on the American popular culture, for the average American, he knew instinctively, wanted entertainment, not high-class art. The book is organized into broad strokes of Four Parts consisting of 22 Chapters, although within this outer structure the author manages to handle the complexities of the development of his themes by sacrificing harmonious adherence to chronology. As the book moves along, a large number of repetitions of earlier material become apparent, especially in Chapter Nine, “The Fantasy Factory.” It is as though the author has chosen to disregard the content of his previous chapters in favor of a quest for new insight by way of serious second consideration. Lengthy subsections within many chapters are consistent in devotion to the biographies of those personally close to Walt Disney, and to the contributions of such great Disney Studio artists as Vladimir “Bill” Tytla, but these subsections would have been better placed within the correct chronological flow. For example, not until near the end of the book, beyond Disneyland, beyond the 1964 World’s Fair, and even beyond EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), does Watts manage to fit in a very important biography, that of Walt’s brother, Roy Oliver, in Chapter 22, taking the reader all the way back to the time of Roy’s birth in 1893.

The book is heavy and overly complex because the author is in essence searching for answers, and is without the secure foundation of deeper understanding from the beginning.

The last paragraph of Chapter 21, which the reader may review by way of briefly postponing another go-round on Watts’s dizzying Disney carousel, is actually one of the most astonishing in the entire book: “The Florida Project [EPCOT] promised to weave together the many threads of the great Disney expansion of the 1960s. On a scope unimaginable even a few years before, it promised to transcend entertainment by entering directly into the social and political realm. Disney’s magic kingdom, it seemed, was about to become a concrete reality as well as a state of mind.” But the great innovator, the Good King of the Magic Kingdom who was absolutely determined to change the woeful circumstances of the Common Folk on Planet Earth, was struck down unexpectedly and quickly and died of lung cancer in 1966.

Author Steven Watts does not really succeed in opening any doors to significant hidden darkness in the personality of Disney, although not for lack of trying, but the avuncular Disney — by Jiminy Cricket! – had only various ambiguous grey areas; he was very much a man of his times. He was happily and faithfully married but once, to Lillian Disney, “who was never cowed by her husband’s volatile moods and iron will.” “Confirmed homebodies, Walt and Lillian occasionally got together with a small circle of friends … while avoiding the nightclubs-and-parties scene.” He smoked, but never around children, drank moderately, and was photographed once at a racetrack with his good friend Charlie Chaplin. Business-wise he did become something of a corporate tyrant in the late 1930s, probably due to enormous responsibilities and financial pressures, but he saw the light after a devastating 1941 strike led by some of his best animators, including, sadly, Bill Tytla. These events were followed by drastic changes at the Burbank Studio wrought by the years of World War II. More »