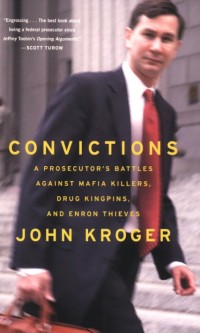

Convictions: A Prosecutor’s Battles Against Mafia Killers, Drug Kingpins, and Enron Thieves

By John Kroger.

By John Kroger.

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2008. Click to Buy this book!

This absorbing 466-page book by former federal prosecutor John Kroger (Assistant United States Attorney, or AUSA) includes a Prologue, Four Parts with 19 chapters, an Epilogue, Sources, and Acknowledgements. The Parts are titled Rookie, Mafia Prosecutor, The War on Drugs, and Enron: White-Collar Crime. The Prologue, titled “Waiting for a Verdict,” opens the book with a description of the most dramatic moments in the trial of the United States v. Scarpa (Gregory Scarpa, Jr.), as the judge receives a note and informs the court that the jury has reached a verdict. Kroger, still something of a rookie in this his third trial — although an extraordinary rookie — writes of his six-month course of preparation, together with trial partner and veteran mob prosecutor Sung-Hee Suh, during which both worked 18 hours a day, seven days a week. The verdict is not revealed until the third chapter of Part II. As it turns out, both the government and the defense had flawed cases, so the jury decided to give each side a partial victory. Scarpa was convicted on all counts except murder; the jury would not convict a man of murder solely on the basis of cooperator testimony.

The entire first part of the book describes the path of John Kroger’s life (b. 1966) that brought him to the moments of the Scarpa verdict. The book’s back cover praise proves absolutely accurate: “… Probably the frankest discussion ever of the extraordinary ethical dilemmas that go with wielding the government’s crushing power over lives.” — Scott Turow. “Kroger wins here as he did in the courtroom — with simplicity and candor, passion and integrity, and a ferocious, persuasive intelligence.” — Susan Choi.

John Kroger chose to become a prosecutor so as to avoid the murky side of defense, when distortions and exaggerations can detrimentally effect inner integrity and the sense for truth. “I wanted to remain in public service, but in a job that offered concrete, measurable results and moral clarity, a job where at the end of the day I would know I had done something useful and ethical. I was not certain, but I thought I had identified that job: prosecutor.” “By 2003 I had become a very good prosecutor. I had also concluded, to my deep regret, that sometimes it is impossible to be both a great prosecutor and a good human being.”

The reader will soon become aware that questions of ethics, morality, right conduct and social good are powerful leitmotifs in this book; these are the continuous guiding threads through the complexities of Convictions, and Kroger scrutinizes his past and how he stands up to these higher measures that he has established for himself: in youth, military service, college at Yale with a major in Philosophy, employment as a legislative correspondent in Washington, D.C., graduation from Harvard Law School, and as an AUSA in the areas of Organized Crime and Narcotics (Eastern District of New York, EDNY, under the Department of Justice). At Yale he enrolled in a course in classical Greek philosophy and read Plato’s Meno. Plato suggests in this brief dialogue, writes Kroger, “… That we can learn to be good people if we devote ourselves to rigorous philosophical self-analysis, submitting our actions and beliefs to close and careful scrutiny. I recall being shocked as I read this simple piece … For me, philosophy was never just a course of study. I passionately believed in what the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik calls ‘the sunny optimism of humanism,’ the conviction that if I read the right books and applied what I learned, I could lead a more perfect life.” Kroger tells us that he never adopted one single philosophical point of view, but borrowed bits and pieces of wisdom from different sources: “From Aristotle, the importance of rigorous, independent, critical thinking; from Aquinas, the value of analytic clarity.” He especially liked the 19th century British utilitarian philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. “Bentham and Mill were concerned with a very basic but critical question: What makes an action ‘good?’ They answered that a person’s actions should be judged by their social consequences.” “… I also liked the emphasis on selflessness. In the Marines I had been taught to place the safety of others before my own well-being.” Even late in the book, the leitmotifs flourish. Kroger asks: What happens if being a good prosecutor requires you to do something you find repugnant? Utilitarianism, he believes, must always prevail in government, “but suppressing our Kantian values, our belief in the sanctity of the individual, may be dangerous.” His work with outer causative factors led him to read The Interpretation of Dreams, by Sigmund Freud. “Freud suggests that some events are ‘over-determined,’ caused by a confusing array of multiple factors, any of which, operating alone, might have been sufficient to make the event happen.”

Although during his years as an AUSA, from 1997 to 2003, where, particularly in Narcotics, his cases could be numbered in the thousands, Kroger hones in on three areas that constitute the greatest threats to the stability of the United States. These areas are pointed out dramatically in the title of the book: Mafia Killers, Drug Kingpins, and Enron Thieves. In the late 1970s, few discerning Americans could fail to be aware of the presence of the mafia in most major cities. It was Ronald Reagan, elected as President in 1980, who finally initiated the government attack on organized crime. Kroger reveals that the government’s extensive antimafia strategies have been successful, but changing social factors have also contributed. “In the second half of the twentieth century, the mafia rose to power because our society provided a particular evolutionary niche, a set of legal, social, and economic conditions, that made it easy for the mob to prosper.” The disturbing factor of immorality that entered into the Scarpa trial was Scarpa’s testimony that he had been on the government payroll for years. “Actually, many of Scarpa’s allegations were true,” writes Kroger in the Prologue.

No effective strategies have been proffered in drug law enforcement, and the dangers of illicit drug trafficking and consumption are on the rise. Kroger writes: “… We are currently trying to combat drug suppliers in an economic and social environment that is tilted heavily against us. In the United States, sixteen million people are prepared to pay heavily for illegal drugs … If the United States really wants to reduce drug abuse, we have to develop a rational well-funded drug treatment plan.” This would be far less costly than, e.g., the current border wars in the Southwest. The sixth chapter of Part III details Kroger’s experiences on September 11, 2001, and the chaotic times that followed.

“White-Collar Crime” is also on the rise and in Part IV Kroger offers an exhaustive account of the recent Enron bankruptcy disaster and the moral erosion of the private or capitalistic segment of the American economy. In 2003, not long after a career change to that of professor of criminal law at the Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, Kroger is called back to duty by the Justice Department; the Department had decided to respond aggressively and thus transferred successful mafia prosecutors to this new battle against corporate crime. Kroger had had serious reservations about the manipulative interrogation techniques he had learned to use in Narcotics, and these techniques only led to errors when applied to circumstances where the defendants simply could not accept the fact that they had committed a crime. The mobsters were easier to understand, comments Kroger. After a year of many 100-hour and longer work weeks on “The Broadband Scam” of the Enron disaster, Kroger had used all of the leave that Lewis & Clark had “graciously” granted him and he returned to Portland. He writes that it took four years to convict two top Enron executives, Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay, while the jury deadlocked in the trial of three Broadband defendants. Incidentally, Kroger adds that Jeff Skilling “… Was ultimately billed $54 million dollars for his defense by the firm of O’Melveny and Myers.” In addition, over and over Kroger refers to the absence of moral character among the Enron folks. “They seemed privileged, dishonest, and unethical, smart enough to game the legal system and sleazy enough to do it… I found their behavior very disturbing, for it seemed as if they had learned nothing from Enron’s collapse. I walked around the FBI office for five minutes, trying to calm down and regain my equilibrium.” He observes that not even a Jesuit education had benefited one individual.

In the Epilogue, titled “New Beginnings,” Kroger looks back on his five years as a professor at Lewis & Clark (with normal 40-hour work weeks that must have made Convictions possible), and expresses his yearning to return to public service – “That desire is in my blood,” he writes. He had made the decision to announce his candidacy for the position of Oregon’s next attorney general.

This book is highly recommended and deserves a permanent place in all libraries. John Kroger can truly be called a modern American patriot. The only questions the anthroposophist might ask, in light of the effectiveness of the inner moral structure and strengths that Kroger has developed within himself from “bits and pieces” of different philosophies, is whether The Philosophy of Freedom and subsequent related works of Rudolf Steiner — especially The Threefold Social Order — were offered in the curriculum of the Yale University Philosophy Department when Kroger was an undergraduate there from 1987 to 1990 (or are presently being offered).

References: The Philosophy of Freedom, also translated as The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, is available on-line at the Rudolf Steiner Archive. The Threefold Social Order is also available on-line at the Rudolf Steiner Archive under the title, Basic Issues of the Social Question, and as a publication from Amazon.com.

For an introductory description of The Threefold Social Order, especially within the legal domain, see the page at http://www.rudolfsteinerweb.com/Threefold_Social_Order.php. — Review by Martha Keltz