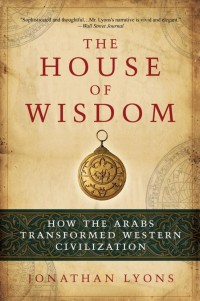

The House of Wisdom: How the Arabs Transformed Western Civilization

By Jonathan Lyons

By Jonathan Lyons

Published by Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2009 Click to Buy this Book!

In the Prologue of The House of Wisdom, titled Al-Maghrib/Sunset, author Jonathan Lyons introduces the central themes that are carried throughout the entire book with unceasing intellectual vigor: “The power of Arab learning, championed by Adelard of Bath [c. 1080–1152], refashioned Europe’s intellectual landscape. Its reach extended into the sixteenth century and beyond, shaping the groundbreaking work of Copernicus and Galileo … Averroes, the philosopher-judge from Muslim Spain, explained classical philosophy to the West and first introduced it to rationalist thought. Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine remained a standard European text into the 1600s. Arab books on optics, chemistry, and geography were equally long-lived. The West’s willful forgetting of the Arab legacy began centuries ago, as anti-Muslim propaganda crafted in the shadow of the Crusades began to obscure any recognition of Arab culture’s profound role in the development of modern science.” A Note to Readers explains the structure of The House of Wisdom, “which pays tribute to the success of Arab scholars in measuring out the ever-changing pattern of night and day that determines the times of the five daily Muslim prayers. The book begins at sunset (al-maghrib prayer), the traditional start of the day in the Middle East; then moves through the nightfall (al-isha) of the Christian Middle Ages; recounts the dawn (al-fajr) of the great age of Arab learning; soars toward the glory of midday (al-zuhr) with our central hero, Adelard of Bath, in the Near East; and concludes with the rich colors of afternoon (al-asr) that mark the end of the Age of Faith in the West and the seemingly unstoppable triumph of Reason.” The four parts that follow the Prologue contain nine chapters. The book is not written in precise chronological order, but there is a chronological listing of Significant Events at the beginning, in addition to a list of Leading Figures, e.g., Albumazar, Boethius, Michael Scot, Ptolemy, Siger de Brabant, and Thomas Aquinas.

The House of Wisdom has a certain quality that is difficult to define and this is most likely due to its unusual structure and underlying tone of reverent enthusiasm, as well as the long, absorbing, even magical journey that it offers through heretofore unfamiliar perspectives of history, that is, from the Westerner’s point of view. Praise for The House of Wisdom includes such descriptions as “sophisticated and thoughtful; vivid and elegant; refreshing; new and important; treasure trove of information; lively and well-researched; highly recommended; complex and fascinating; riveting, breakneck pace; wonderful; clear and accessible; complex, humane and intricately beautiful.” From the Guardian: “In this clear and well-written book, Jonathan Lyons delves into all sorts of musty corners to show how Arabic science percolated into the Latin world in the Middle Ages and helped civilize a rude society.” None of this praise is exaggerated, and all reviewers would agree: educational renewal for deepening understanding of Arab history, Islam and the Muslim way of life is essential and critical in our time, in this second decade of the 21st century and far beyond. It is hard to imagine anyone more capable than Jonathan Lyons of facilitating this process. When the initial readings of The House of Wisdom are completed, it can serve as a first-rate reference book that will never become outdated.

The Bayt al-Hikma or the House of Wisdom refers to the royal library within the Round City of the Abbasid Empire — Baghdad — that had been established along the western banks of the Tigris River by the Caliph Abu Jafar al-Mansur, with the work of construction “along Euclidean lines” completed around 765. “Over time, the House of Wisdom came to comprise a translation bureau, a library and book repository, and an academy of scholars and intellectuals from across the empire.” “Even diplomacy, and on occasion its cousin war, was harnessed to the drive for greater knowledge. Abbasid delegations to the rival Byzantine court often conveyed requests for copies of valuable Greek texts, successfully securing works by Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, and Euclid. A copy of Ptolemy’s astronomical masterpiece, soon famous among the Arabs, and later the Latins, as the Almagest, was said to be one of the conditions of peace between the two superpowers.” Abdallah al-Mamun, son of Harun al-Rashid, became the seventh Abbasid ruler after defeating his half-brother al-Amin through four years of civil war. Al-Rashid had died in 809. Al-Mamun was Caliph of Baghdad from 813 to 833, and it was probably around 813 that al-Mamun had his dream of Aristotle: “According to Ibn al-Nadim, the sleeping caliph spotted a bald, light-skinned Aristotle sitting on his bed. Overcoming his initial shock at finding himself face-to-face with the great philosopher, al-Mamun asked him to define ‘that which is good.’ Aristotle replied that reason and revelation — that is, science and religion — were both good and in the public interest, a response the caliph took as confirmation that scientific scholarship was a religious duty. ‘The dream,’ Ibn al-Nadim concludes, ‘was one of the most definite reasons for the output of books.’”

From the beginning of Chapter Four, Mapping the World: “Al-Mamun’s great Abbasid Empire owed much of its enormous vitality to the spiritual and intellectual energies unleashed two hundred years earlier in a remote corner of the Arabian Peninsula. There, in 610, a former caravan driver and small-time merchant began to receive revelations from God during periodic retreats in the nearby mountains. After receiving his initial revelations, Muhammad was troubled and at first told no one, except his beloved wife Khadija. But he was soon commanded by God to make his message public: ‘O you enveloped in your cloak, arise and warn’ (Koran 74:1-2).” The Prophet Muhammad’s birth date, c. 570, occurred at a very propitious time for bringing a high civilization into the world. The years from the end of the Roman civilization in 476 until 800, when Charlemagne, as victorious Holy Roman Emperor, established Christianity as the principal religion of western civilization, are years that some scholars refer to as the “Dark Ages” of Europe. During this time period the Muslim culture took root and flourished. The European situation only darkened further, and in the year 1095 Pope Urban II “appealed to the princes of Christendom … in the French town of Clermont to end their ceaseless warring and turn their murderous energies on the unbelievers of the East.” Thus began the first of the Crusades. “They couldn’t even tell the time — this uncountable army of believers,” comments Jonathan Lyons in the first sentence of the book, referring to the followers of Peter the Hermit, the common people, and to the noblemen and knights who followed.

Adelard of Bath was born into a prosperous family that enabled him to be “a model country gentleman,” but he saw little value in the contemporary world and despaired at the state of Western learning in particular. “… I judge the ancients eloquent, and call the moderns dumb.” — he wrote in On the Same and the Different. He pursued higher education in the cathedral school of Tours, France, taught at Laon, then traveled to southern Italy, the formerly Muslim island of Sicily, and the lands of the Crusades. By 1109, still dissatisfied with his level of learning, he “set off alone for the rumored intellectual wonders awaiting in the Arab East.” He was in Antioch during the earthquake of 1114. By 1126 he returned to the medieval West with the intention of spreading the knowledge he had gained from Arab culture, including astrology, astronomy, geometry, mathematics and philosophy.

Adelard introduced the astrolabe (pictured on the book cover) to Europe with the publication of his treatise On the Use of the Astrolabe. The astrolabe was about the size of a salad plate and was “beautiful to behold,” fashioned in bronze with intricate detail and polished. “Degrees of latitude, or perhaps the hours of the day, were commonly inscribed along the outer edge.” The sun’s annual path as well as celestial information could also be determined from the astrolabe. It was held aloft, suspended at arm’s length by a ring at the top. “Arab tradition … credits the great astronomer [Ptolemy] with the accidental invention of this powerful tool. Ibn Khallikan, writing in the thirteenth century, recounts one version: Ptolemy was out riding one day, a celestial globe in his hand; he dropped it, and his horse crushed it flat with his hooves, creating the planispheric astrolabe.”

In the final chapter of the book the author writes of Thomas Aquinas [1224–1274] and his work with great admiration: “For Thomas, only a few areas were off-limits to philosophy, and then only because man could never hope to penetrate the mysteries of the divine will. He found just three articles of faith that could not be proved by reason and that had to simply be accepted by all Christians: God’s creation of the world at a specific time; the Trinity; and Jesus’s role in the salvation of mankind. By implication, virtually the entire natural world and even what might appear to be traditional theological questions — for example, regarding God’s existence — were proper subjects for the philosophers and could be adjudicated by reason. For Thomas, as for Averroes before him, philosophy and religion could never truly contradict each other.”

The House of Wisdom is the second book of Jonathan Lyons. Answering Only to God: Faith and Freedom in 21st-Century Iran, co-authored with Geneive Abdo, was published in 2003, and Islam Through Western Eyes: From the Crusades to the War on Terrorism is a 2012 publication. – Review by Martha Keltz